A Man in a Hurry

Thomas Shillitoe's mental and spiritual struggles

In the present day we are used to examining and often speaking freely about our mental health but this practice was less common in the past. However for Thomas Shillitoe his spiritual struggles and his lifelong mental health problems were all part and parcel of his religious life.

Thomas Shillitoe was born in Holborn, London, in February 1754, the son of Richard and Frances Shillitoe, both members of the Church of England, who gave their sons a religious upbringing and kept them ‘close indoors’ away from outside influences. This was possible while Richard was employed as librarian to Grays Inn but when Thomas was twelve his father, suffering from bad health, moved the family to Islington where he took over the running of the Three Tuns public house. This was an unwise choice as Thomas and his brothers were exposed to much temptation and bad company and his father found himself totally unsuited to his new life. After a few years the venture failed and the family was able to return to Grays Inn.

Thomas was apprenticed to a grocer at the age of sixteen but his master drank and the business failed. Finding another, sober, master Thomas settled down, made the acquaintance of a distant relation who had connections with Quakers and began to attend Friends' meetings with him. He confesses that his motives were not altogether pure as he went mainly to be with his relation who also took him to dinner and to afternoon entertainments. As time went on however Thomas felt more and more at home in Gracechurch Street meeting and committed himself to membership, adopting plain dress and plain speech.

Thomas’s decision to stand out in this way enraged his father, and was not acceptable to his master either. Thomas was forced to leave his situation and hoped to live with his parents but, as he reports, his father told him

He would rather follow me to my grave, than I should have gone amongst the Quakers; and he was determined I should quit his house that day week, and turn out and “quack” amongst those I had joined myself in profession with.

Thomas’s problems with his family and employer came to the notice of Friends and one in particular, a motherly woman called Margaret Bell, actively interested herself on his behalf. She found Thomas what she assumed would be a congenial situation in a Quaker bank in Lombard Street where he would be surrounded by associates with the same views as his own. Thomas began with high hopes but was soon disillusioned as he found his sober-seeming fellow clerks ‘as much given up to the world and its delusive pleasures as other professors of the Christian name.’ His conscientious scruples were also offended by the bank’s practice of buying lottery tickets for clients.

Thomas felt that he had to find another way forward that would allow him to make a living independently without being asked to act against his conscience. Many Friends thought that he was foolish to contemplate giving up his good material prospects in the bank but when he consulted Margaret Bell she, although concerned for his welfare, advised him to look at the matter simply and mainly in the light of how it would affect his religious journey.

This made things clear to Thomas who resolved to follow only his inward Guide in all his ‘future steppings’, left his job at the bank and trained as a shoemaker. Thomas learned steadily and began to support himself but at this point his health broke down and he was advised to move to the country. In 1778 when he was twenty-three Thomas moved to Tottenham, then a country village, where he found a welcoming Quaker community. Among them he also found a wife, Mary Pace, who was eight years older than himself and with whom he went on to have seven children.

Thomas needed these steadying influences for he was subject throughout his life to severe nervous depression and anxiety. By his own account his state of mind could be 'a pit of horrors' and he says that he was twice confined to his bed from the sudden sight of a mouse. While crossing London Bridge he would run for fear that it would collapse under him. Sometimes, for weeks on end, he believed himself to be a teapot, living in dread of anyone coming near him in case they should break him.

Although his health improved when he moved to Tottenham he consulted doctors about his nervous complaints for another twenty years and diligently followed their advice. These medical men, as was common practice at the time, prescribed a diet of beefsteak with a liberal supply of wine and ale at dinner and supper. When Thomas became worse they advised him to smoke and to take spirits and water but the only effect of this was to cause him to lose sleep on top of his other ailments. For this the doctors prescribed laudanum, a mixture of opium and alcohol then widely used. Beginning with ten drops a day this quickly became ineffective so they increased the dose little by little until Thomas was taking 180 drops each night!

Unsurprisingly Thomas's health did not improve and he says,

I went about day by day frighted by fear of being frighted - a dreadful situation indeed to be living in.

Eventually, around 1800, he decided to turn his back on the doctors, rely entirely on God's help, and give up all his stimulants at once, as he had found that gradually changing things did not work. He became a total abstainer and also took no animal food except milk and eggs. His health improved, although his nervous disposition never entirely left him.

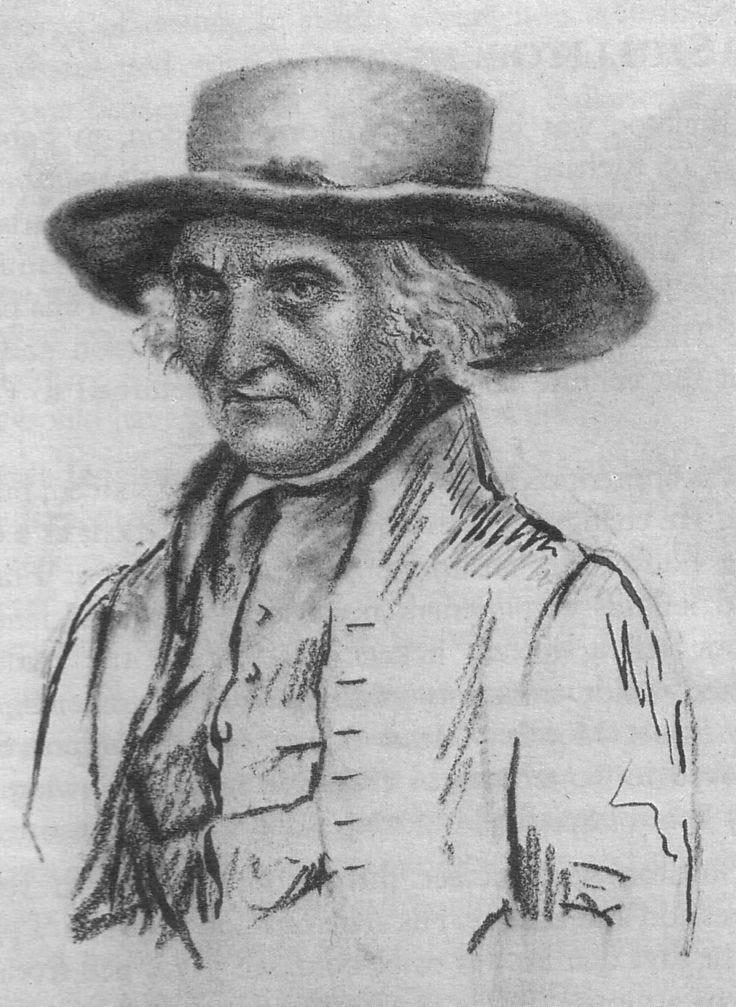

Thomas was recorded as a Quaker recorded minister in 1790 and travelled extensively in the UK. Unusually for the time he always travelled alone, perhaps because no compatible companion could be found. Thomas was careless of his appearance, walking everywhere very fast with his coat over his arm and his hat sometimes balanced on his umbrella. He was impatient of any delay and could not abide inactivity, preferring to work in the fields when opportunity arose rather than take any rest.

Thomas felt increasingly led to travel in this way and, when his business was successful enough to support his family, he organised his affairs so that in 1806 at the age of 52 he was able to retire from business and devote himself to his Quaker ministry.

His travels now took him farther afield. Speaking from his own experience he became a tireless campaigner for temperance before many of his fellow Quakers took up the cause and in 1808 and 1811 visited Ireland where he preached against the evils of alcohol in hundreds of whiskey shops, often encountering violent opposition.

In 1821 Thomas felt called to visit Europe and asked his meeting for approval which was given although he spoke no foreign languages and would be travelling alone and mainly on foot as usual. Thomas trusted that interpreters would be found when needed and this was generally the case. He set out on his year-long journey, going to the principal towns of Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Switzerland and France. In every place he visited he went first to the prison and then to the palace and was usually well received in both establishments for his forthright open cheerfulness and goodwill which was directed equally to everyone he met.

In 1824 Thomas visited the continent again, going to Germany, Denmark and on to Russia. In St Petersburg, although subject to anxiety about being arrested as a spy, he was able to meet privately with Tsar Alexander I. This was a deeply affecting encounter for them both at which they knelt together in prayer. On his return home Thomas was shocked to hear of the Tsar’s death the following year. His son-in-law tells of hearing Thomas in an upper room pacing back and forth in his distress at the news.

Thomas delivered several plain-spoken addresses to British monarchs and George IV never forgot his encounter with 'that little Quaker.' Thomas went with his friend Peter Bedford, to deliver an address asking for greater public morality to William IV and his Queen. He told the Friends to whom he submitted it for inspection, 'There must be no lowering it as with water, it must be all pure brandy' - an interesting choice of words for a temperance campaigner.

In 1826, when he was over seventy, Thomas felt compelled to leave his family yet again and set off for America. The visit was fraught with difficulty as Thomas found himself embroiled in the controversy with Elias Hicks which was splitting American Quakers. Hicks claimed Thomas as a supporter without his consent and this made the three-year visit very dispiriting for the aging man so that he returned home with a sense of failure.

Thomas tried to follow his Inward Guide but his mental troubles sometimes worked against this. Although affable and cheerful to all classes of people Thomas could also be irritable and impatient with those who disagreed with him. He did not hold back in his admonitions to his fellow Quakers to avoid the growing worldliness and love of gain which he saw everywhere, and on one occasion at Yearly Meeting grew so excited and violent towards an opponent that he had to be forcibly removed by two Friends. His particular friends, such as Peter Bedford, understood and supported him but did not hold back from advising him to change his behaviour.

On his return home to Tottenham in 1830 Thomas concerned himself with the welfare of the poor and aged in his area, raising money for almshouses and other good causes. He would appeal directly to the local gentry for funds, asking for specific amounts of money, and was seldom denied. He lived with his wife near the meeting house and regularly attended meeting there until just before he died in 1836 at the age of eighty-two.

I see Thomas Shillitoe as an example we can follow for his dedication to his religious path but also because of the weaknesses which were part of his spiritual journey and which he never completely overcame. He was plain-speaking and irritable, impatient and generous, eccentric and faithful, a family man and a dedicated Friend. He deserves to be remembered for everything he was.

Thank you for sharing this. Many years ago I worked for a descendant of Francis Shillitoe, his 4x great grandson if I’m correct, called Francis George Shillitoe, a 3rd generation Solicitor and Coroner in Hitchin, Hertfordshire

The is very interesting background to the story in the blue book, Christian Faith and Practice, about his visit to Spandau prison. The prisoners were known for their violence and at first he decided not to take his penknife, but on reflection he deliberately put it back in his pocket, deciding to rely on Divine Providence.